TDD anti-patterns - episode 4 - The greedy catcher, The sequencer, Hidden dependency and The enumerator - with code examples in javascript, python and php

The content here is under the Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license

This is a follow up on a series of posts around TDD anti-patterns. The first of this series covered the liar, excessive setup, the giant and slow poke, those four are part of 22 more anti-patterns listed in the James Carr post and also discussed in a stackoverflow thread.

Do you prefer this content in video format? The video is available on demand in livestorm.

In this blog post we focus on four more: The greedy catcher, The sequencer, Hidden dependency, and The enumerator. Each addresses a specific aspect of code that makes testing harder. These patterns arise either from insufficient Test-Driven Development practice or from limited experience in software design.

The greedy catcher

Exception handling is challenging. Some developers advocate avoiding exceptions entirely, while others use them to signal errors. Despite your programming style, testing for exceptions can reveal patterns that contradict the test-first approach. In the previous episode, we examined the secret catcher. Now we’ll look at its cousin, the greedy catcher.

The greedy catcher appears when the subject under test handles the exception and hides useful information regarding the kind of the exception, message or stack trace. Such information is helpful to mitigate possible undesirable exceptions being thrown.

Next up, we have an example from a possible candidate for the greedy catcher, this piece of code was extracted from the project Laravel/Cashier stripe - Laravel is written in PHP and is one of the most popular projects in the ecosystem, the following code is a package that wraps the stripe sdk into a Laravel package. Despite having a try/catch handler inside the test case (that could potentially point to further improvements), when the exception is thrown, the test case catches it and asserts some logic:

public function test_retrieve_the_latest_payment_for_a_subscription()

{

$user = $this->createCustomer('retrieve_the_latest_payment_for_a_subscription');

try {

$user->newSubscription('main', static::$priceId)->create('pm_card_threeDSecure2Required');

$this->fail('Expected exception '.IncompletePayment::class.' was not thrown.');

} catch (IncompletePayment $e) {

$subscription = $user->refresh()->subscription('main');

$this->assertInstanceOf(Payment::class, $payment = $subscription->latestPayment());

$this->assertTrue($payment->requiresAction());

}

}

The greedy catcher arises not only in the test code, but also in the production code, hiding useful information for tracing back an exception is a source of time spent that could have been much less. The following example is a representation of a javascript middleware that parses a JWT token and redirects the user if the token is empty - the code uses jest and nuxtjs.

Line 1 decodes the JWT token using jwt-decode package. If successful, the middleware proceeds, otherwise, it invokes the logout function (lines 2-3).

As far as the code looks, it is difficult to note that under the catch block, the exception is being ignored and if something happens, the result will be what the logout function returns (line 3).

export default function(context: Context) {

try {

const token = jwt_decode(req?.cookies['token']); // 1

if (token) {

return null;

} else {

return await logout($auth, redirect); // 2

}

} catch (e) {

return await logout($auth, redirect); // 3

}

}

The test code uses some nuxtjs context to create the request that is going to be processed by the middleware. The single test case depicts an approach to verify if the user is being logged out if the token is invalid. Note that the cookie is behind the serverParameters variable.

it('should logout when token is invalid', async () => {

const redirect = jest.fn();

const serverParameters: Partial<IContextCookie> = { // 1

route: currentRoute as Route, $auth, redirect, req: { cookies: null },

};

await actions.nuxtServerInit(

actionContext as ActionContext,

serverParameters as IContextCookie

);

expect($auth.logout).toHaveBeenCalled(); // 2

});

The tricky part here is that the test above passes as it should, but not for the expected reason. serverParameters holds the req object that has cookies set to null (line 1), when that is the case, javascript will throw an error that is not possible to access a token of null, as null if not an array or object. Want to try out this behavior in javascript?

Such behavior, executes the catch block, that calls the desired logout function (line 2). The stack trace for this error won’t show up in any place, as the catch block ignores the exception in the production code.

You might be wondering that this is something acceptable, as the test passes. Therefore, there is an even further catch for this kind of scenario.

The greedy catcher - root causes

- Poor exception handling design—catching exceptions too broadly without re-throwing or logging

- Insufficient understanding of what exceptions to catch and how to handle them effectively

- Testing without examining error paths during test-first flow

The sequencer

The sequencer brings light to a related subject that was covered in the testing assertions post (in this case, using jest as a testing framework). More specifically, the section about Array Containing depicts what the sequencer is.

In short, the sequencer appears when an unordered list used for testing appears in the same order during assertions. In other words, giving the idea that the items in the list are required to be ordered.

Simple Example: Checking Unordered Lists

Here’s a common scenario where the sequencer anti-pattern appears:

// Fetching a list of user IDs (order doesn't matter for functionality)

function getUserIds(roleFilter) {

return [123, 456, 789, 101];

}

// THE SEQUENCER: Assuming a specific order when order doesn't matter

test('should fetch user ids', () => {

const result = getUserIds('admin');

expect(result[0]).toBe(123); // Order-dependent!

expect(result[1]).toBe(456);

expect(result[2]).toBe(789);

expect(result[3]).toBe(101);

});

The problem: If the order changes (e.g., due to database optimization), the test fails even though the functionality is correct—all required users were returned.

Better approach: Use arrayContaining for unordered lists

test('should fetch user ids', () => {

const result = getUserIds('admin');

expect(result).toEqual(expect.arrayContaining([123, 456, 789, 101]));

});

This assertion passes regardless of order, as long as all expected IDs are present.

Complex Example: Checking Unordered Data Structures

The following example shows the sequencer in practice with more detail:

const expectedFruits = ['banana', 'mango', 'watermelon']

// THE SEQUENCER: Position-dependent assertions

expect(expectedFruits[0]).toEqual('banana')

expect(expectedFruits[1]).toEqual('mango')

expect(expectedFruits[2]).toEqual('watermelon')

As we don’t care about the position, using the utility arrayContaining might be a better fit and makes the intention explicit for further readers.

const expectedFruits = ['banana', 'mango', 'watermelon']

const actualFruits = () => ['banana', 'mango', 'watermelon']

expect(expectedFruits).toEqual(expect.arrayContaining(actualFruits))

It is important to note that arrayContaining also ignores the position of the items and also if there is an extra element. If the code under test cares about the exact number of items, it would be better to use a combination of assertions. This behavior is described in the official jest documentation.

The example with jest, gives a hint on what to expect in code bases that have this anti-pattern, but the following example depicts a scenario in which the sequencer appears for a CSV file.

def test_predictions_returns_a_dataframe_with_automatic_predictions(self,form):

order_id = "51a64e87-a768-41ed-b6a5-bf0633435e20"

order_info = pd.DataFrame({"order_id": [order_id], "form": [form],})

file_path = Path("tests/data/prediction_data.csv") // 1

service = FileRepository(file_path)

result = get_predictions(main_service=service, order_info=order_info)

assert list(result.columns) == ["id", "quantity", "country", "form", "order_id"] // 2

On line 1 the CSV file is loaded to be used during the test, next the result variable is what will be asserted against and on line 2 we have the assertion against the columns found in the file.

CSV files use the first row as the file header separated by commas, in the first row is where the name of the columns are defined and the lines below that follow the data that each column should have. If the CSV happens to be changed with a different column order (in this case, switching country and form), we would see the following error:

tests/test_predictions.py::TestPredictions::test_predictions_returns_a_dataframe_with_automatic_predictions FAILED [100%]

tests/test_predictions.py:16 (TestPredictions.test_predictions_returns_a_dataframe_with_automatic_predictions)

['id', 'quantity', 'form', 'country', 'order_id'] != ['id', 'quantity', 'country', 'form', 'order_id']

Expected :['id', 'quantity', 'country', 'form', 'order_id']

Actual :['id', 'quantity', 'form', 'country', 'order_id']

In this test case, the hint is that we would like to assert that the columns exists regardless of the order. In the end, what matters the most is having the column and the data for each column regardless of its order.

A better approach would be to replace line 2 previously depicted by the following assertion:

assert set(result.columns) == {"id", "quantity", "country", "form", "order_id"}

The sequencer is an anti-pattern that is not often caught due to its nature of being easy to write and the test suite is often green, such an anti-pattern is unveiled when someone has a hard time debugging the failure that is supposed to be passing.

The sequencer - root causes

- Unclear test intent—misunderstanding what should be tested (data vs. order)

- Overreliance on array index-based assertions instead of value-based matching

- Insufficient knowledge of testing framework assertion utilities (arrayContaining, etc.)

Hidden dependency

The hidden dependency is an anti-pattern popular among developers, in particular, the hidden dependency frustrates developers and dampens their enthusiasm about testing in general. It can be the source of hours debugging the test code to find out why the test is failing as it sometimes gives little to no information about the root cause.

Hint: if you are not familiar with vuex or the flux pattern, it is recommended to check it out first.

The example that follows in this section is related to vue and vuex, in this test case the goal is to list users in a dropdown. Vuex is used as a source of truth for the data.

export const Store = () => ({

modules: { // 1

user: {

namespaced: true,

state: {

currentAdmin: {

email: 'fake@fake.com',

},

},

getters: userGetters,

},

admin: adminStore().modules.admin, // 2

},

});

On line 1, the structure needed for vuex is defined, and on line 2, the admin store is created. Once the stubbed store is in place we can start to write down the test itself. As a hint for the next piece of code, note that the store has no parameters.

it('should list admins in the administrator field to be able to pick one up', async () => {

const store = Store(); // 1

const { findByTestId, getByText } = render(AdminPage as any, {

store,

mocks: {

$route: {

query: {},

},

},

});

await fireEvent.click(await findByTestId('admin-list'));

await waitFor(() => {

expect(getByText('Admin')).toBeInTheDocument(); // 2

});

});

On line 1 we create the store to use in the code under test and on line 2, we try to search for the text Admin, if it is in the text we assume that the list is working. The catch here is that if the test fails to find the Admin, we will need to dive into the code inside the store to see what is going on.

The next code example depicts a better approach to explicitly use the data needed when setting up the test. This time on line 1, the Admin is expected to exist beforehand.

it('should list admins in the administrator field to be able to pick one up', async () => {

const store = Store({ admin: { name: 'Admin' } }); // 1

const { findByTestId, getByText } = render(AdminPage as any, {

store,

mocks: {

$route: {

query: {},

},

},

});

await fireEvent.click(await findByTestId('admin-list'));

await waitFor(() => {

expect(getByText('Admin')).toBeInTheDocument();

});

});

In general, the hidden dependency appears in different ways and in different styles of tests, for example, the next example depicts a hidden issue that comes from testing the integration with the database.

def test_dbdatasource_is_able_to_load_products_related_only_to_manual_purchase(

self, db_resource

):

config_file_path = Path("./tests/data/configs/docker_config.json") // 1

expected_result = pd.read_csv("./tests/data/manual_product_info.csv") // 2

datasource = DBDataSource(config_file_path=config_file_path)

result = datasource.get_manual_purchases() // 3

assert result.equals(expected_result)

The test setup uses configuration files and CSV data. The CSV file (line 2) is critical since the result must match its content.

Inside this method, there is a query that is executed in order to fetch the manual purchases and assert that it is the same as the expected_result:

query: str = """

select

product.id

po.order_id,

po.quantity,

product.country

from product

join purchased as pur on pur.product_id = product.id

join purchased_order as po on po.purchase_id = cur.id

where product.completed is true and

pur.type = 'MANUAL' and

product.is_test is true

;

"""

This query has a particular where clause that is hidden from the test case, thus making the test failing. By default the data generated from the expected_result sets the flag is_test to false, leading to no results returning in the test case.

Hidden dependency - root causes

- Insufficient test isolation—tests depend on external state (database, files, configuration)

- Lack of test data management strategy—unclear what data is required for each test

- Inadequate use of setup/teardown methods or test fixtures

The enumerator

Enumerating requirements in a brainstorm session usually is a good idea, it can be handy to create such a list for later consumption, those can even become new features for a software project. As in software we are dealing with features it seems to be a good idea to translate those in the same language and order, so the verification of those becomes a checklist.

As good as it might sound for organization and feature handling, translating such numbered lists straight to code might bring undesired readability issues, and even more for test code.

As weird as it might sound, enumerating test cases with numbers is a common behavior I have seen among starters. For some reason, at first, it seems a good idea for them to write down the same test description and add a number to identify it. The following code depicts an example:

from status_processor import StatusProcessor

def test_set_status():

row_with_status_inactive_1 = dict(

row_with__status_inactive_2 = dict(

row_with_status_inactive_3 = dict(

row_with_status_inactive_3b = dict(

row_with_status_inactive_4 = dict(

row_with_status_inactive_5 = dict(

New developers inevitably ask: what does 1 mean? What does 2 mean? Are these the same test? Being explicit about what is being tested is crucial. Research has shown that this is a common issue when generating test cases automatically to cover code execution paths (Daka et al., 2017).

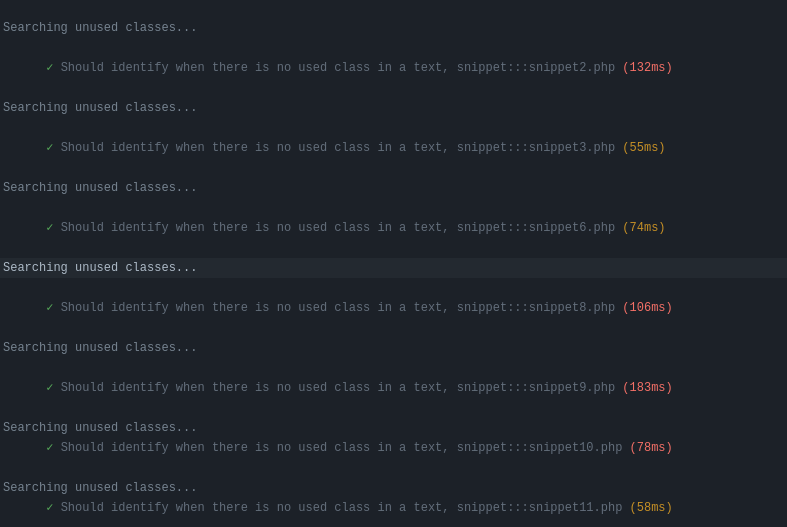

The first example was in python, but this anti-pattern arises in different programming languages. The next example in typescript is another type of enumerating test cases, in this scenario, the test cases are file names that are used to run the tests.

Enumerating test scenarios obscures business patterns behind numbers, making test intentions unclear. Additionally, when tests fail, error messages provide only numbers, not context about the failure’s root cause.

The enumerator - root causes

- Lack of naming discipline—developers resort to enumeration when they can’t articulate what each test does

- Missing understanding of test method naming conventions and their importance for documentation

- Insufficient domain knowledge—unable to describe test scenarios in business terms

Wrapping up

Episode 4 deepened our exploration with four patterns that address specific testing challenges: exception handling, assertion clarity, hidden state dependencies, and test naming.

Pattern Relationships

These four anti-patterns clearly relate to earlier episodes:

- The Greedy Catcher extends The Secret Catcher (Episode 3)—both deal with exception handling, but Greedy Catcher hides information in production code

- Hidden Dependency mirrors Excessive Setup (Episode 1) and The Generous Leftovers (Episode 2)—all involve managing test state

- The Sequencer complements The Nitpicker (Episode 3)—both are assertion-focused smells

- The Enumerator signals broader design issues like The Dodger (Episode 3)—both stem from testing implementation rather than behavior

Practical Checklist

When writing tests for Episode 4 issues:

- Are you catching exceptions or logging them? (Greedy Catcher)

- Do assertions check order when order doesn’t matter? (Sequencer)

- Can a test run in isolation, or does it depend on shared state? (Hidden Dependency)

- Is each test method name descriptive or numbered? (Enumerator)

- Could you rename your test method without breaking understanding?

We have now covered 12 of 22 anti-patterns. The journey continues with Episode 5.

Appendix

Javascript code

Copy and paste this snippet to reproduce the error in javascript when trying to access a property of null:

const req = { cookies: null }

req?.cookies['token']

Edit Jan 21, 2021 - Codurance talk

Presenting the tdd anti-patterns at Codurance talk.

Related subjects

References

- Daka, E., Rojas, J. M., & Fraser, G. (2017). Generating unit tests with descriptive names or: would you name your children thing1 and thing2? Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis, 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1145/3092703.3092727

Changelog

- Feb 15, 2026 - Grammar fixes and minor rephrasing for clarity