A friendly introduction to Git

The content here is under the Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license

Join Our Community

Connect with developers, architects, and tech leads who share your passion for quality software development. Discuss TDD, architecture, software engineering, and more.

→ Join SlackGit has stabilized itself as the de-facto standard versioning control system, developers got used to it (despite it being a not-so-newbies welcome tool) and Git has an ecosystem that helps to ease the learning curve. GitHub has emerged as an open-source platform, and GitLab is an integrated DevOps platform that runs based on Git.

Git is used for code analysis to provide insights for decision-makers. Tornhill used git to construct code analysis that reveals hot spots in the code based on criteria such as design issues and knowledge silos (Tornhill, 2018). Through git, those become data-driven and visually accessible.

In the next section, we will dive into the history of Git, how it intersects with SVN, and the differences between both Version Control Systems.

What is Git, and why should I use it?

In the early days of software development, programmers used to write code and push it to a main server. This worked great in the ’90s and, believe it or not, it still does nowadays, but of course, there are more elegant solutions to today’s software development.

Linus Torvalds, the Linux creator, had a big issue when he was trying to develop other systems and keep them versioned. From this point on, he decided that he would end the software only when he had a good versioning system, and then Git was born.

Back in the day, SVN was the main version system used by programmers and it was like a main server where you could push all your code to it.

SVN’s centralized architecture with client-server operations. Source: https://bhrugeshblog.wordpress.com/tag/subversion/

SVN’s centralized architecture with client-server operations. Source: https://bhrugeshblog.wordpress.com/tag/subversion/

The image above shows it very clearly to us: it is a main server where every client has the entire code. It is a copy and paste in each client machine. The arrows on the right side are the operations that developers do in a common repository. Updates mean that each client machine will get only the fresh new version from the main server, and the commits are what each client does before pushing code to the server.

The big problem with SVN(Subversion) is that it doesn’t work in a distributed way, you can only have a main repository where it needs to be online, SVN is even more complex because each commit is an entire “photograph” of the entire repository. This means that even if you change one single line in your code base, SVN will “take a photograph” of your entire repository and it makes it hard to sync.

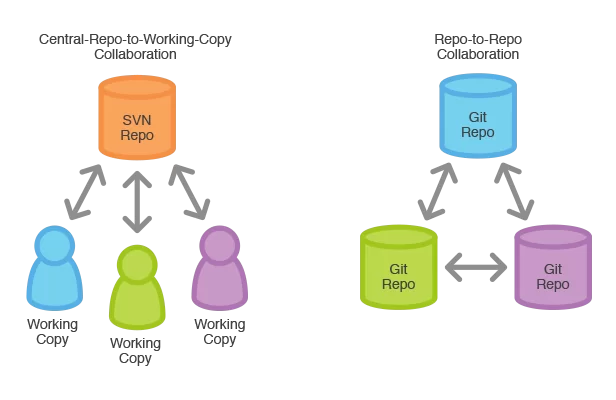

Git is a distributed system for collaboration among programmers. It makes versioning easy, and the collaboration works better. Git works oppositely compared with SVN. It is distributed instead of having one single point, which means that every client can be a main server.

Git also takes care not to create a new copy of all files when a change occurs to a single file. It’s smart enough to send to the server only what has been changed.

Git features

In this section, we are going to examine essential Git features and how to properly use them. If you are new to Git, you must read this section. If you are not, I’d recommend reading it just to review the content. Git has different features ranging from the most basic ones such as commit, clone, push, and pull to the more advanced ones: cherry-pick, rebase, and bisect. You don’t need to memorize each of those commands but rather understand what the purpose of each one is and what problem it tries to solve.

First, understanding the repository is the key to proceed. “Repository: a place, building, or receptacle where things are or may be stored.”

Reference: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/repository

On the one hand, the dictionary says that a repository is a place where we can store something. On the other hand, to us in the computer scope, it is an abstraction. Indeed, a repository is where we store things, but in Git, it means the source code (you can store any kind of data with git, but for simplicity let’s assume only source code), the repository is where the source code stays and is pushed to.

One of the chapters of Peter Goodliffe’s book is dedicated to Version Control Systems, and he uses git as an example - but it could be any other, i.e. Mercurial or SVN. He says that every programmer should master their skills with version control and also tells us a little story about what he had been through with a team that didn’t use a version control system.

The team usually sends the code to an email at the end of the week after a long week of coding, he calls it “Distributed Data Loss”.

If you think it is something absurd to send source code through an email, what advantages do we get using a Version Control System? Peter has answered it in the following items from his book (page 171) (Goodliffe, 2014):

- It provides a central backup of your work.

- It provides the developer with a safety net. It leaves room to experiment, try changes, and roll them back if they do not work.

- It fosters a rhythm and cadence of work: you do a chunk of work, test it, and then check it in. Then you move on to the next chunk of work. For example, a single git init command in a directory establishes a Git repository in a heartbeat.

- It enables multiple concurrent streams of development to occur on the same codebase without interference.

- It enables reversibility: any change in the history of the project can be identified and reversed if it is found to be wrong.

-

Code review integration: Modern development practices emphasize code review for quality assurance and knowledge sharing. Version control systems provide the foundation for review workflows, with platforms like GitHub and GitLab integrating review tools directly into the version control interface (Bacchelli & Bird, 2013).

-

Continuous integration enablement: Version control serves as the trigger point for automated build, test, and deployment pipelines. CI/CD systems monitor repository changes to initiate validation workflows, establishing rapid feedback loops that reduce integration risk (Fowler & Foemmel, 2006).

Learning Resources and Interactive Tools

For those new to Git, Learn Git Branching offers an interactive, gamified introduction to Git concepts. This approach addresses Git’s documented learnability challenges through visualization and progressive complexity, reducing the frustration often experienced by newcomers (Spinellis, 2012).

Installing Git and Getting Started

Installation

Git requires installation on your development environment. The official Git documentation provides platform-specific instructions:

- Official installation guide: https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Getting-Started-Installing-Git

- Windows: Git for Windows includes Git Bash, providing Unix-like command-line interface

- macOS: Available via Xcode Command Line Tools or Homebrew (

brew install git) - Linux: Distributed via package managers (

apt-get install git,yum install git, etc.)

Command-Line Interface vs. Graphical Tools

While numerous graphical Git clients exist (GitHub Desktop, GitKraken, Sourcetree), learning Git through the command-line interface offers several pedagogical advantages:

- Conceptual clarity: CLI commands directly correspond to Git operations, making the underlying model explicit

- Platform independence: Command-line skills transfer across operating systems and environments

- Scriptability: CLI enables automation and integration into development workflows

- Comprehensive functionality: GUI clients typically expose subsets of Git’s capabilities; CLI provides complete access

Research on programming education suggests that learners who master command-line tools develop stronger mental models of underlying systems (Robins et al., 2003). For production workflows, graphical tools may enhance productivity once conceptual foundations are established.

Verifying Installation

In a terminal window, running the command git --version should display the installed version:

git version 2.45.0

Post-installation, configure your identity (required for commit authorship):

git config --global user.name "Your Name"

git config --global user.email "your.email@example.com"

Additional configuration options are documented in the official Git configuration documentation.

Further Reading and Related Topics

This introduction establishes foundational knowledge for Git usage. Related topics covered in subsequent sections include:

- Git Internals: Deep dive into Git’s object model, packfiles, and internal data structures

- Git Bisect: Binary search debugging technique for identifying regression-introducing commits

- Synchronizing Branches: Strategies for keeping branches updated in distributed workflows

- Managing Configuration: Repository-specific settings and multi-repository workflows

For comprehensive coverage, consult Chacon and Straub’s Pro Git (Chacon & Straub, 2014), freely available at https://git-scm.com/book, or Loeliger and McCullough’s Version Control with Git (Loeliger & McCullough, 2012).

References

- Tornhill, A. (2018). Software Design X-Rays: Fix Technical Debt with Behavioral Code Analysis. Software Design X-Rays, 1–200.

- Goodliffe, P. (2014). Becoming a Better Programmer: A Handbook for People Who Care About Code. " O’Reilly Media, Inc.".

- Bacchelli, A., & Bird, C. (2013). Expectations, outcomes, and challenges of modern code review. 2013 35th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE), 712–721. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSE.2013.6606617

- Fowler, M., & Foemmel, M. (2006). Continuous integration. Thought-Works.

- Spinellis, D. (2012). Git. IEEE Software, 29(3), 100–101. https://doi.org/10.1109/MS.2012.61

- Robins, A., Rountree, J., & Rountree, N. (2003). Learning and teaching programming: A review and discussion. Computer Science Education, 13(2), 137–172. https://doi.org/10.1076/csed.13.2.137.14200

- Chacon, S., & Straub, B. (2014). Pro Git (2nd ed.). Apress. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4842-0076-6

- Loeliger, J., & McCullough, M. (2012). Version Control with Git: Powerful Tools and Techniques for Collaborative Software Development (2nd ed.). O’Reilly Media.